Decades of research has led many educators to believe that, in general, people learn more effectively through explicit instruction than self-driven discovery. However, this research has consistently lacked clarity on fundamentals and skewed its definitions to fit school systems, rather than fitting the broader goal of enhancing learning.

In the most common style of experiments, the researcher sets a specific learning target in advance and then some boundaries within which learners must search to find it.

The following story shows the major flaws in this approach.

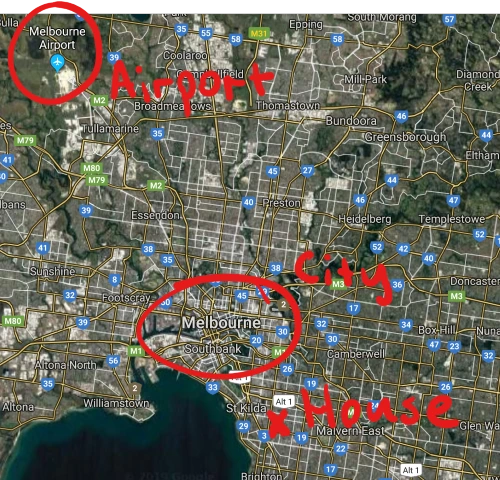

Say you invite two foreigners to your city and ask them to find your house, but you only give one of them your address. The other person has to discover where you live.

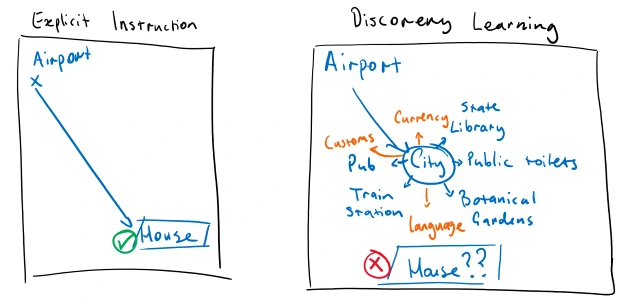

In this setup, the odds are wholly in favour of the explicit approach, in which the visitor with your address could simply hire a vehicle straight from the airport to your house.

Without your address, the other visitor would have to find and use information in much more creative ways. For example, they might use a map to identify residential areas and then cross-reference those areas with clues from the invitation you sent them, or from your social media profile.

On the other hand, if they were never that interested in finding your house to begin with, they might exert some independence by choosing a different target for themselves. For example, after reaching the airport they might catch the first train to the city and start enjoying the popular landmarks. Eventually they would need to find food to eat and a place to stay for the night, which would inevitably involve navigating the local language, customs and currency.

With either of these approaches, the explorer could easily fail to reach your chosen target, despite learning a whole lot more about your city.

Unfortunately, none of that learning would be recognised or rewarded because it had not been already enshrined as the learning objective for that day.

At the conclusion of the experiment, based solely on the success criterion of "Who got to the house first? ", the explicit approach would win, despite the clear loss of overall learning.

While experiments of this type have long been used to discredit discovery learning, they have never actually measured overall learning. Instead, they've only considered specific, hand-picked targets, achieved within the narrow time-frame of the experiment. If getting to the house was part of a job with real consequences - like delivering a postal package - then winning that race would have value. If not, then the importance of achieving a single, narrow objective must be compared to the loss of all the serendipitous learning that is forgone.

Although this scenario may seem extreme, it fairly represents the basic principles used in real experiments. Even if the scenario was more reasonable, the core problem would persist: No matter how big or small the target is, all learning beyond it would be devalued or completely invalidated, even when it has obvious value in other contexts.

Although this critique is about the approach used in experiments, the underlying philosophy actually originates from the classroom. The reason why experiments use predefined targets is because teachers have predefined curriculums to program into their students' heads.

However, until researchers question the underlying frameworks in education - including the very existence of predefined learning outcomes - they will only be able to tell us what works within those frameworks. They will never be able to tell us how those frameworks can be improved.

While predefined learning targets can give nice immediate results, they inherently stifle true discovery and broader learning. To move forward, we must first appreciate how much learning is quietly destroyed through the relentless regime of predefined targets - whether in experiments, lesson plans or entire curriculums. Then we can begin to support overall learning, by valuing the diverse and unanticipated outcomes that naturally result from independent exploration.